Disciplining Children – What It Means, Why Discipline Is Important, And Tips On Doing It Correctly

Unfortunately, the word “discipline” appears to have become synonymous with punishment, but that’s not what it’s all about at all.

The word has its roots in the Latin verb that means to teach or train, and that’s key to understanding what discipline should be, and the best ways to do this.

A parent’s role in raising children is, of course, multi-faceted.

For example, there are tasks, such as keeping your child healthy, fed and safe, which are all focused on the here and now – you need to do these things every single day.

And then there are longer-term goals, such as making sure your child is prepared and able to live independently, when the time is right. This includes knowing the difference between right and wrong, respecting boundaries, and understanding cause and effect (i.e. if you do this, then this will happen).

Discipline is largely part of the latter group of parental responsibilities, and getting it wrong can have long-lasting consequences – whereas getting it right teaches your child the best type of discipline, which is self-discipline.

So What Is Discipline?

Discipline is all about providing guidance to your children, teaching them about which behaviours are acceptable and which are not.

It also includes helping them learn about boundaries and consequences.

Children want and need boundaries to help them learn, and according to Dr. Kevin Leman, “My years of counseling parents and children have shown me that in a permissive environment, kids rebel. They rebel because they feel anger and hatred toward their parents for a lack of guidelines and limit setting.”

This does not mean, of course, that children won’t push those boundaries, because they will.

However frustrating this may be for parents, this is normal – it’s part of the learning process.

As adults, we should recognize that the world is not black and white – some boundaries have a degree of flexibility, while others do not. And we also understand that exceeding those limits can have repercussions. For example:

- If you murder somebody (and are found guilty), you can reasonably expect to at least be sent to jail.

- If you break the speed limit in your car and are stopped by the police, there may be extenuating circumstances (e.g. a medical emergency) that will lead to your not being prosecuted, or there may be no valid reason for speeding in which case you can reasonably expect to be fined and/or lose your driving licence.

So, to summarize, children need limits, and it’s the parents’ responsibility to set them.

Types Of Discipline

There are, broadly speaking, two approaches to disciplining children:

- Aversive (e.g. yelling and spanking).

- Positive (e.g. focusing on the positive behaviours more than the negative ones).

Aversive Discipline

There are plenty of studies that show the harmful effects of aversive discipline.

For example, children subjected to spanking may demonstrate:

- aggressive behaviour (because you’ve already shown them that hitting people is OK)

- mental health problems

- substance abuse

- trust issues (because the people they think love them the most are hurting them)

- violence toward their partner

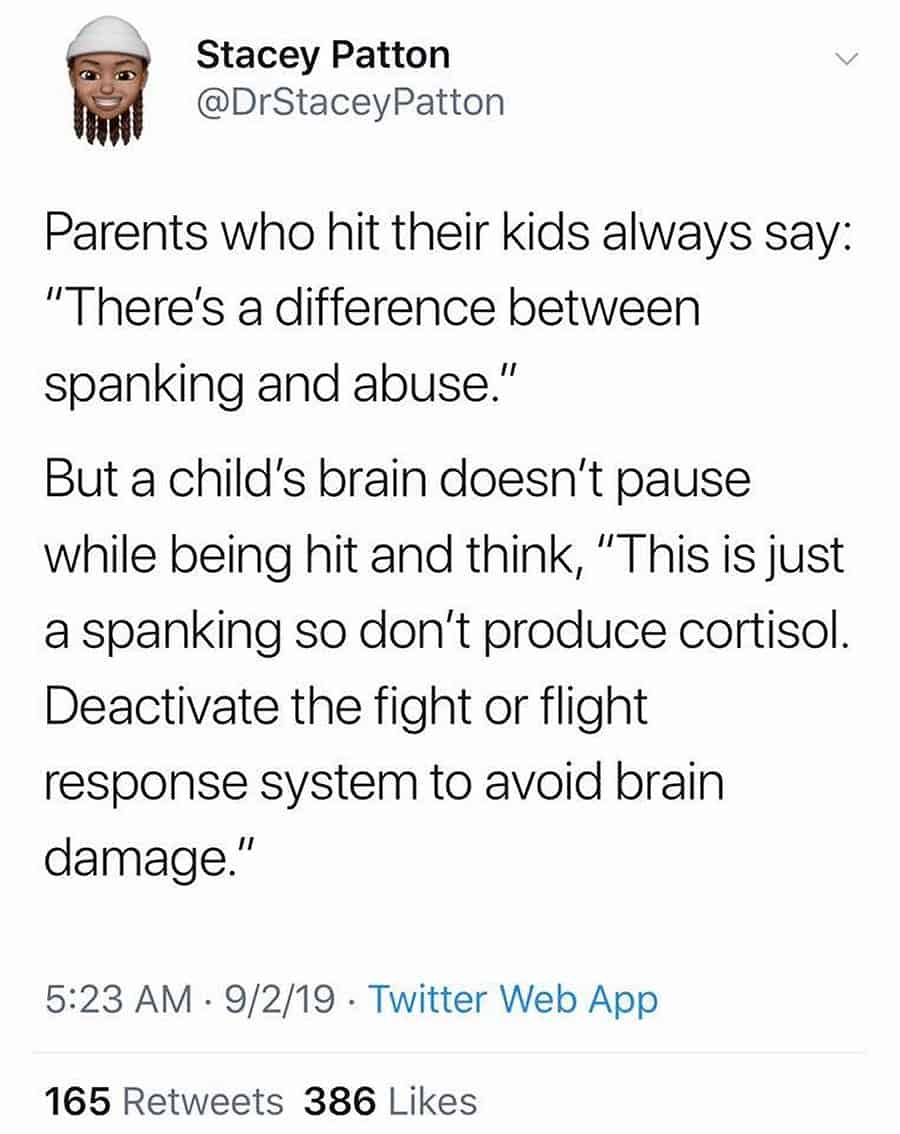

Some people try to claim that spanking is different to child abuse, and from a parent’s perspective, this may be true. After all, it’s not your intention to abuse your child – you’re just “teaching them a lesson”.

But a child’s perspective is very different, and it’s summed up by the following, which I happened to see on Facebook shortly before writing this article:

However, it’s worse than that, because one study showed that the “benefits” (e.g. stopping the unacceptable behaviour) of corporal punishment tend to be very short-lived: almost three quarters of children resumed the behaviour they’d just been punished for within ten minutes.

And yet the psychological effects can be extremely long-lived.

To a lesser degree, constantly yelling at your kids can have the same effects as spanking.

(This isn’t to say that you should never yell – we all know how children can sometimes drive parents to distraction and beyond – but it should not become your first and only recourse.)

In summary, aversive discipline can (sometimes) create an obedient child (although this may increase their rebelliousness later on), but do you really want a child who obeys you only out of fear?

The good news is that spanking, and other forms of corporal punishment, appears to be on the decline (in the USA, at least).

Positive Discipline

The problem with aversive discipline is that the only thing it really teaches your child is that if they repeat the behaviour that led to them being spanked or yelled at, they will get spanked or yelled at again (i.e. punished).

But it doesn’t teach them anything truly useful.

So, if aversive discipline is generally not a good way to react to your children’s unacceptable behaviours, then the other option is positive discipline.

At the heart of positive discipline is the idea that there are no bad children – there are only good and bad behaviours. (Yes, there are probably exceptions to this, but that does not invalidate the general principle.)

For example, if you yell at your child and call them a “bad girl” or “naughty boy”, it helps reinforce the idea that they are intrinsically bad people.

With positive discipline, you’re not punishing them and you’re not cementing the idea that they themselves are bad – you’re trying to help them understand why what they did or said was wrong, as well as different and better approaches to dealing with that situation in the future.

Benefits Of Positive Discipline

So, what are some of the benefits of adopting a positive disciplinary approach?

- Improved emotional maturity.

- Fewer power struggles (between parents and children, or between siblings).

- Less bad behaviour.

- More pleasurable childhood memories.

- Reduced tension in the house.

- Stronger parent / child relationships.

Positive Discipline Tips

I hope I have shown how a positive approach to discipline is better, not just for the children but for the parents too, so what are some useful strategies and tips to go this route?

- Set clear limits. Your children need to understand which behaviours (e.g. hitting somebody else, stealing, lying) are not acceptable.

- Be consistent. If you have a house rule, then “no” should mean “no” every single time.

- Explain the consequences of breaking those rules. There is no point having a limit or rule if there is no consequence for exceeding or breaking it. You therefore need to make it crystal clear what will happen if that rule is broken.

Needless to say, that consequence must be something they dislike (e.g. taking their phone away, removing television privileges, time-outs in a quiet spot).

- Carry through on your threats. Again, making threats (e.g. if you hit your sister, you will have to go and sit by yourself for ten minutes) is of no benefit to anybody if you do not carry through on them. Your child will find it more difficult to grasp the relationship between cause and effect, and they will lose trust in you (because you promised you would do something, and then you went back on that promise).

Making empty threats will only cause you much larger problems in the long run!

- Don’t overdo the rules. It’s better to have a small number of rules that you deem ultra-important, and have your children obey those rules all the time, than a lot of rules that they do not (and maybe cannot) comply with consistently. In other words, pick your battles and focus on the most important rules only.

- Repetition. One way to find out whether your child understand the rules (and consequences) is to ask them to repeat the information back to you. If they get it wrong, this is your chance to correct them, so there is no ambiguity, and if they get it right, then they cannot later claim that they didn’t know what that rule meant.

- Involve your children. Where practical, involve your kids in creating the rules and, maybe, agreeing suitable consequences. You can even get them to sign their name to it (if they’re old enough) once you’ve all agreed, as a family, what those rules will be. Being involved will make them feel more responsible and increase the chances of them abiding by what you all, as a family, agreed.

- Post the rules. Since as I said above, there shouldn’t be a large number of rules, then post them somewhere where they are visible to everybody.

- Incentives. Offering or giving an incentive (e.g. an extra bedtime story, helping make an ice cream dessert, a trip to the playground, or even a hug) for good behaviour is one way to help your child learn.

Note that this is not the same as bribery! Bribery is often a last resort to get your child to comply, when all other methods have failed, and in this situation, it’s actually your child who is in control of you. Incentives, on the other hand, are agreed up front, so the child knows what to expect.

- Watch your words. When disciplining your child, be careful of the words you use. You want to avoid, for example, words that might belittle or embarrass or shame your child – regardless of whether other people are present or not.

- Don’t let your children play one parent off against another. This one can be tricky, especially if you are separated from the other parent, but you need to be consistent in applying the rules. If one parent says “No” but the other says “Yes”, you’ve got problems on your hands. You need to have each other’s backs at all times.

- Offer choices. We all know that when we are given a free choice, it helps us to feel in control. The same goes for children, so if they have done something unacceptable, offer them choices as to how they want to deal with (e.g. “Would you rather go and apologize to that child or would you rather sit with me and read for a few minutes?”) – and then ensure you follow through on which option they choose.

- Keep your voice even. However hard this may be, most of the time it is advisable not to raise your voice. (An obvious exception if your child’s safety is at risk.)

- Demonstrate correct behaviour. Where practical, actually show your child what behaviour would be acceptable.

- Encourage empathy. If your child has just hit somebody, ask them how it felt the last time they were hit, and whether they liked it or not. Teaching them to think about how their actions affect others will go a long way to them becoming a kind human being.

- Rephrasing. By this, I mean don’t use full sentences or commands, but try single words, or short questions. For example, rather than saying in a stern voice, “Shut the door”, try casually, in your normal, friendly voice, saying “door?”.

Or try “Where are you meant to put your dirty clothes?” instead of “Put your dirty clothes in the laundry basket!”

Done in this way, there is little (or nothing) to rebel against.

- Be wary of the silent treatment. Used correctly, this can be a good disciplinary technique, but used inappropriately, it can cause resentment, for example.

The best way to use this is to explain to your child that you will ignore his behaviour if he does certain things (e.g. scream) and that you will only engage with him when he talks calmly.

This is actually an example of setting limits and defining the consequences – if he screams, you will ignore him until he stops screaming – and therefore offers an opportunity to learn good behaviour.

- Acknowledge their feelings. Telling your child that you understand they feel angry, sad, frustrated, etc. is a good first step toward helping them understand their emotions and how to deal with them. It also shows that you care about and are listening to your child.

- Set clear expectations. One way to minimize the risk of bad behaviour is to make it clear how you expect your child to behave before the situation or event arises. For example, saying, in advance, “When we get to the restaurant, you need to sit quietly at the table and not run around” can be very effective.

- Get to the root cause. Sometimes, your child’s behaviour is because they are simply testing the limits, but sometimes, they appear to act out but it’s really because they cannot easily express what they are feeling. When you spend time talking to your child about what’s going on, and what they are feeling, and why they did what they did, you will uncover something useful that may be a valuable lesson for both you and your child.

- Parental time-outs. Sometimes, when you feel like you’re about to explode, then assuming your child is safe, why not give yourself a time-out (i.e. time to calm down, count to ten, and decide on a better course of action than yelling, for example)?

Caveats

There are a few more things I think you should be aware of:

- The percentage of young children who are obedient increases as they grow older. With two-year-olds, you can expect them to comply with your requests about 60% of the time. This increases to 70% when they hit three, and for children who are five, it can be anywhere from 80% – 95%.

- One Dutch study showed that children alter how they best learn once they reach a certain age: children younger than 12 learn best via positive feedback, while older children flip-flop and learn best via negative feedback.

- Whatever your house rules are, there will always be situations that are not covered. In these cases, you need to use your best judgement, try to be consistent with your existing rules and what you have done in the past, don’t give in to impulse (e.g. by yelling or hitting), and consider whether you need to update your rules.

Conclusion

Effective parenting is hard – I don’t think anybody who has children will doubt that – but you do need to balance immediate needs (e.g. keeping your child safe) with the larger picture (e.g. raising a responsible adult).

There is a term that has become popular, called “credit card parenting”, and what this means is that sometimes parents will do something in the short term (which is equivalent to an impulse buy they can’t really afford) that will cost them more in the long term (because they end up paying interest on that purchase).

You therefore need to be aware of the impact of disciplinary decisions you make today – there is little benefit in putting a stop to bad behaviour today if it increases it in the years to come.

And yes, this does often mean you have to adopt what looks like a “tough love” approach, and you may feel like a monster for not giving in to your child’s tantrums, but again, focus on the end game.

Additional Resources

These are suggestions for those who wish to delve deeper into any of the above:

- How To Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Will Talk

- Effective Discipline To Raise Healthy Children